Sydney – can one place better epitomize mankind’s egregious sin as well as her capacity for redemption? In the middle of January 1788, the first fleet of settlement ships landed on the coast of the massive continent at Botany Bay, which Captain Cook had suggested as an ideal settling place when he explored there in 1770. Finding Botany Bay ill suited for settlement, Captain Arthur Phillip sailed down the coast a bit and found that Cook had overlooked the area known as Fort Jackson. Far from a tiny inlet, as Phillip sailed inward he discovered one of the greatest natural harbors in the world and the city of Sydney was born.

Sydney on a beautiful sunny day

Hyde Park Barracks from convict times

A full half of the contingent of 1,500 settlers were convicts sent from Britain. Why was Britain sending so many convicts to Australia? The answer is twofold. First is the so-called “Bloody Code”, the legal system in Britain at the time that carried the death penalty for over 222 crimes,

including cutting down a tree, stealing goods worth 5 schillings (scarcely above the cost of a loaf of bread), or stealing fish from a river. The legal system was so draconian (particularly towards the poor) that magistrates often downgraded the punishment to transportation rather than death in an effort to circumvent the code. Convicts were also sent for political reasons. For example, nearly a 1/3 of the early convicts sent to Australia were Irish Catholics whose land had been taken during the Protestant “settlement” of Ireland (see the

Fields of Indulgence Post “Weeping Buddha, Smiling Buddha” for more insight into this issue). At that time in Ireland, strict laws prevented Catholics from traveling more than 5 miles from their home, entering university, or being able to vote. Many were forced to a life of crime to survive – crimes punishable by transportation off the island or death. Other convicts sent included pirates, pickpockets, and women with “loose morals” (

who often were just women who had intentionally offended authorities in order to travel with their husbands).

The 2nd reason for the large shipment of convicts to Australia (nearly 160,000 people in total between 1788 and 1868, when penal transportation ended) was that a certain colony now called the United States of America had rebelled and stopped accepting the transportation of prisoners that England had previously sent to its shores.

Sydney Harbor Bridge and Opera House

The sins of Sydney’s past didn’t stop with the largely unjust transportation of convicts, but also lie in the terrible way they were treated in the first years. Many arrived to the continent half starved and quickly died while those who survived could be beaten mercilessly or hung for minor offenses while the female population of convicts was routinely sexually exploited.

But perhaps life for the convicts wasn’t so bad compared to the treatment of the Aboriginal populations. Having declared the land “terra nullius” (land belonging to nobody) due to the lack of agricultural activity present on it, the British essentially justified the invasion and destruction of the native population, who had lived there for an amazing 60,000 years prior to any Europeans arriving. The Aboriginal population consisted of over 250 distinct tribes, each with different languages and customs. Captain Cook, upon his discovery of the natives, speculated they might be happier than Europeans. Maybe it’s not surprising when the average aboriginal week consisted of about 20 hours of hunting/gathering with the rest of the time devoted to arts, music, and social activity. Granted living conditions were arduous, but could Europeans have learned something from this simple living rather than just destroying it for their agrarian machine?

Didgeridoo art display in Museum of New South Wales

Unfortunately, early friendly reactions towards the Europeans by the Aboriginals (who thought the settlers were ancestors returned as ghosts – after all they were quite white) quickly turned sour as the colonists intentions became clear. There was to be competition for resources and land and the locals were ultimately considered to be in the way. Early efforts by Governor Phillip to mediate with the locals (

most notably by kidnapping, acculturating and later befriending an Eora tribesman named Bennelong) eventually fell apart as smallpox decimated the local population, leaving hundreds of native bodies floating in the harbor in the early years. As Europeans continued to settle on Aboriginal land, guerilla warfare broke out and hostility would rule the day from then onward.

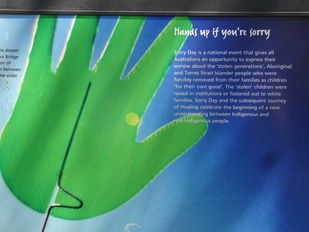

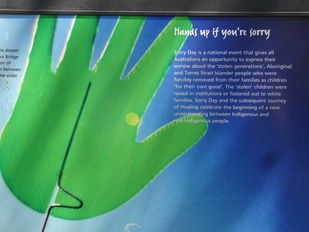

National Sorry Day

This violent attitude towards the Aboriginal population may have reached its most disgraceful point between

1910 and 1970, when nearly 100,000 children were forcibly removed from their Aboriginal families to be placed in mixed-race children in orphanages, boarding schools or white homes. The idea was to promote assimilation, but the end result was to cut the children off from their culture, leaving them alienated both from their own people and the foreigners with whom they were thrust. This “stolen generation” has left a gaping wound in aboriginal culture today and has left many native people disenfranchised, unemployed, and isolated as they have been moved off the land they traditionally roamed upon to be put onto government-run reserves (if your from America this sounds familiar). In fact, it wasn’t until the 1960s that Aboriginal people were even included in the national census and began making strides towards equality in the eyes of the law.

We’ve taken some time to examine the sin at the heart of Sydney’s history, but there are tales of redemption as well. By 1822 nearly half of the convicts who had been transported established themselves as landowners or tradesmen once earning their freedom through good behavior. James Squire, a convict transported on the first fleet for stealing several chickens, was to become the first man to cultivate hops on the continent. Squire ran a tavern, a butcher shop, and a credit union and his death in 1822 saw the largest funeral ever held in the colony, completing his move from “shame to fame”.

His name is now attached to a brand of craftbrews in Australia. In fact, the move from “shame to fame” is something that many Australians take pride in today. It is considered quite “vogue” to have had a convict in your family history. It is proof that your ancestors turned things around in this new world down under.

In regards to the Aboriginal population, redemption is a continuing process whose end result is far more murky than the turnaround the convicts achieved. The government has now recognized a National “Sorry” Day (later renamed the National Day of Healing) that has seen both whites and aboriginals joining together to recognize the injuries done and start the path towards healing. Though much can be said for the power of an apology, the question remains how a nation can ever recover from such violence?

Goldrush Life Exhibit

For Neda & me, Sydney was a welcome return to the big city after the rural adventures in New Zealand. Upon arriving, our generous couchsurfing host Gav cooked us up some kangaroo steaks (didn’t think I would eat a kangaroo prior to seeing one live in the wild!) and introduced us to the city. The next few days saw us walking the city as we explored the beautiful botanical gardens, the Hyde Park Barracks (where convicts were originally housed in the colony), and a fascinating exhibit at the Library of New South Wales on the Goldrush in Sydney. The discovery of gold in 1851 in Victoria would launch a massive goldrush on the continent, bringing in the wealth necessary to develop Sydney and Melbourne into the large cosmopolitan cities they are today.

Kangaroo Steaks courtesy of our Couchsurfing Host - Gav

We enjoyed some of that cosmopolitan spirit on our 2nd night in town with a visit to Victoria park for some slacklining with the locals followed by a hilarious improv comedy show at the University of Sydney, where we sampled the James Squire beer mentioned previously. Of course no visit to Sydney is complete without several different viewpoints of the architecturally stunning Sydney opera house and Sydney harbor bridge, which makes it the most beautiful harbor that we have ever seen. But beyond the bridge and opera house, the harbor is a truly massive affair, stretching 19km inland and providing access to many different areas via ferry. Neda and I took a day to explore one such area when we took the ferry to Manly beach and walked the harbor coastline from the Spit Bridge back to the city. We enjoyed sweeping harbor views as well as our first introduction to some interesting Australian wildlife like the St. John’s cross spider and the big water lizards living along the coast.

Fish market scallops

We ended our time in Sydney with a visit to the local fish market where we sampled barramundi for the first time and delicious fresh scallops grilled in the shell! We also visited the wonderful museum of New South Wales, which features Aboriginal art as well as quirky exhibits displaying a variety of modernist and post-modernist art.

Our time in Sydney was a combination of appreciation for the society that has been built here and a feeling of deep loss for the civilizations that were displaced and destroyed. Still, Australia today is more multi-cultural than ever as it continues to work towards reconciliation with its first people, welcomes refuges from around the world and integrates its Asian neighbors into the cultural mix. It is a country working to fight its reputation as a “cultural backwater” by embracing the arts and globalizing its strong economy. It is a country that continues to strive towards a deeper awareness of the sins of its past while building a brighter future for all of its people. Redemption isn’t a tale that is told overnight, but rather a road that is laid brick by brick. There are many more bricks to lay, but at least the road is under construction.

Sunset Cruise in Sydney

RSS Feed

RSS Feed